Pioneering in the scout movement never sounded a very romantic branch of the game, but it always made an appeal to me. The pioneer really comes into his own when the troops are operating away from base. He must choose, lay-out, maintain, and eventually clear-up any camp-site. This in no way diminished the responsibility of any troop member for camp cleanliness, but it did eventually pin responsibility down to one body, which is always an advantage where discipline must be maintained.

The pioneers’ duties are by no means simple. Take the siting of a camp. One could try standing on a slope of the COTSWOLDS and saying “That’s a nice view — I think we’ll choose this”. A good site needs more than a view. After installation, someone would soon enquire “Why do we have to go so far for wood?” or “Couldn’t we have got nearer to water?” No, there are many small matters to consider and decide; but although it did not lack its practical day-to-day content, the job always had a certain amount of romance for me. Anyway, they gave me plenty of pioneer work to do in the 7th, maybe because, being a teacher, I had a little more time to spare, and pioneering demanded it.

For one thing, it involved transportation, the moving of the camp gear, tents, kits, not to mention a considerable amount of stores, necessary for the initial feeding of the troop. This, of course, later became relatively simple; but in the early days, finding some means of transport that could be spared at that time of year to do our relatively unimportant jobs was by no means easy, particularly as we had to run everything on a shoestring.

The immediate problem was to get the kit and camp equipment for three patrols to the eastern edge of CLEEVE COMMON some five miles away, and the vehicle I found was a farm cart and horse. This I felt would do the job and at the minimum of expense. But my knowledge of the care and welfare of a horse was nil. Of course it would not be very long in our care and in that period our ministrations for its welfare would be minimal. They should, nevertheless, be correct. Eventually it was decided that some chances must be taken. After all, many people with no greater intelligence than us, we opined, managed horses without disaster. There was nothing the matter with the cart and as far as we could tell that went for the horse.

So we started on our pilgrimage and along the tar-macadamed road nothing could be simpler, even the west slope of CLEEVE HILL – certainly a bit more trying for the horse – presented no real difficulties.

When we were over the top of CLEEVE, the road dropped comfortably down to Winchcombe. But if you wished to reach the POSTLIP estate, about half way down you took a sharp right-hand turn, and here the macadamed road gave out. Now we were on rough and very ready COTSWOLD surfacing.

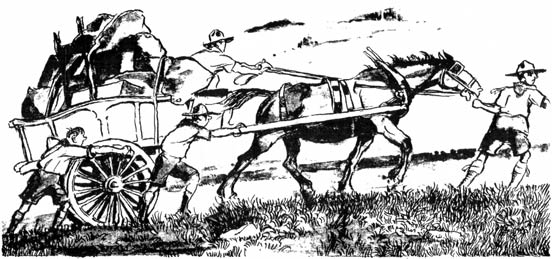

For a while the road, tho’ rough, was reasonably level as it skirted the side of the Common, but the gradient soon increased. The horse’s pace slackened, his grip of the road was less sure, and the energy demanded by this trying bit of terrain grew greater each yard we progressed. We shouted, we encouraged, we exhorted the horse in a language we fondly imagined he understood, but our overall progress was not encouraging. We grabbed the wheels and did our best to add some minor propulsion. But it was all to little avail. The frequency with which we applied large stones to stop the backward run at a halt, proved we were fighting a losing battle. Not only was the horse not equal to the job – he was also showing signs of distress already. His shoulders hung, his knees were bent, and his nostrils covered his head in steam. What could we do? It was unthinkable to go all that way back with our goal almost in sight. But we were at the end of our resources.

Then came one of those silences. For a very short period, all was still. “Twenty minutes silences” my mother used to call them. For no explicable reason, if you looked at the clock, the hands were at “twenty minutes to” or “twenty minutes past”! We all looked up the road where, coming down towards us were a man and a boy. The boy may have been a farm-hand, the man was not. He carried a thumb-stick and wore what was probably the Englishman’s uniform of the day – flannels and a brown tweed coat. As I say, there was a momentary pause. The man stepped forward, caught one glimpse of the horse, and then all hell broke loose. He cursed us as an incompetent bunch of ignorant amateurs, bungling a professional job at the distressing expense of a dumb animal.

Since my early and innocent days, T cannot say that I have known the more eloquent of the drill-sergeants of this planet, but I have known a number. They are an awe-inspiring race and those of my own country have earned themselves a proverbial standing with other adorners of our native tongue. In this oration I detected an Irish accent, but little else. I had never been over-protected from the hurly-burly of school inter-communication. But here my mind was being assaulted by verbal missiles quite unrecognisable to me.

He cursed us and described our ancestors – or lack of them – in no complimentary manner. He dissected our intellects and laid bare our hypercritical love of animals. He towered above us and his command of distorted English was frightening. He did everything but breathe fire. Posed as Lucifer Incarnate, he accused us of breaking every rule in the decalogue – and then invented some for this special occasion!

Loss of breath alone forced him to stop. He turned to the boy and gave an order, and the boy disappeared.

The effect of all this upon us scouts was devastating. We were not only speechless but could scarcely move. We were in a state of shock. Never had we known behaviour or heard language like this, in our lives. He handed his thumb-stick to me, deftly unhitched the horse, and drew it from the shafts. Then he let it loose on the grass and regained his stick.

There was a short wait when we didn’t know what to do or where to look, and just shuffled our feet nervously, when over the hill returned the boy leading two cart horses harnessed tandem fashion. The horses were soon attached to the cart, the strain tested, and the boy looked towards the man. It was then the man spoke to me “I suppose you are the scout lot for the Paddock, up by the Common?”

“Yes” I said.

“Well”, said he “We’ll see you there. You bring the horse. I’m Mr. FOSTER’s bailiff. Now let’s get going.”

So he solved our difficulty and we returned our transport. I tried to thank him but it wasn’t an easy matter.

POSTLIP was a very interesting village, the farm in good condition, and the farming excellent. The bailiff knew something more than distorted English! The manor was Elizabethan, yes, black and white, timber and brick, and even planned in the traditional ‘E’. But the gem was the small late Norman church, built during that lawless time of STEPHEN in ENGLAND when “men said openly that Christ and all his saints slept”. Now, I believe, it was owned by Mrs FOSTER who kept a part-time priest there and ran it as an assistant chapel to the Roman Catholic church of Winchcombe. In fact Mrs FOSTER, herself a staunch catholic, had (I suspected) built up a strong little Catholic community.

One afternoon she paid us a special visit and generously invited us all to the manor to tea on Saturday. She then said that no doubt most of our boys were Church of England, but if they felt they would like to go to church on the Sabbath, there was a nice short late afternoon service, BENEDICTION, and she would be glad to welcome them. In gratitude we could not but accept, and so, there was I, on Sunday afternoon, taking a spruced-up section of the Company down to the little Norman church.

They made us welcome, they made us comfortable, and seated us in a small loft overlooking most of the ground-floor of the chancel and nave – probably where the orchestra sat in days gone by. The worshippers were seated quietly in their seats – a low organ voluntary filled the church, hardly louder than an insect’s hum. Then even the organ died away and for a while it was a perfect summer’s afternoon.

Suddenly a loud chord on the organ brought us all to our feet and our eyes were riveted on the doors at the side of the chancel. They swung open and thence in a blaze of colour, a whisper of music, and a haze of heavenly perfume, stepped forth a resplendent acolyte and attendant altar boys. Stately their walk as rhythmically swinging their censers they stepped at the head of the procession. It was as if we in the COTSWOLDS had for a moment been granted a fleeting view of some heavenly pasture. My company was transfixed, wide-eyed and incredulous. It was not that the wave of an angelic wing had swept them. Theirs was a different mental image. They swung round to me, interrogative and incredulous. What were they seeing? Couldn’t I also see? their eyes enquired. That was no acolyte. That was the incarnate Beelzebub that had accosted us on the Cotswolds the week before! What was he, bailiff, Lucifer, or angel?

But I will say this —- not one of them let me down —- no one giggled.

The loft settled down, the service continued, all was as it should be, and I pondered on the explanation the boys most certainly would demand of me. What could I say? Eventually I’ve no doubt I should dodge the questions as Hamlet did —- “There are more things in heaven and earth than are dreamed of in your philosophy”.

Extract from Charlton Kings Local History Society Autumn 1982 Volume 8 pages 2-4 Author: George Hyland